Case study: Get dark command windows all the time in Windows 10

Update (25/5/2021): Another strategy: try finding 0f8588eb0100 and replacing with 0f8488eb0100.

TL;DR

- Make a copy conhost.exe from System32.

- Open it with a hex editor (I use HxD).

- In HxD, go to Search - Find - Hex-values.

- Search for 881d9e530a004885c07477ff15b32e08009084c0.

- In Windows 10 version 2004, replace ff15b32e0800 with 909090909090. If using Windows 10 version 20H2, replace ff15b32e08009084 with 9090909090909090.

- Save file and copy it back to System32 (take ownership of original conhost.exe in order to replace it).

- Profit!

Synopsis

This short write-up provides information on how to combine a series of techniques in order to correctly patch an executable. It provides an overview of a couple of operating systems concepts, and how to approach analyzing a similar problem. Although showcased on Windows, the principles mentioned here apply to any modern operating system. Extensive experience is not required with any of the following methods that are presented in the article:

- Static analysis of executables (article uses Ghidra as a disassembler)

- Debugging closed source executables (article uses Microsoft’s debugger in Visual Studio)

- Developing the right train of thought when analyzing closed source binaries

- An overview of the role and explanations regarding choices for a few security mechanisms that most operating systems and applications implement nowadays (the article touches on Address Space Layout Randomization, Position Independent Code, Control Flow Guard)

- Binary patching

- An inside on how the mechanisms the Windows operating system provides regarding theming, in particular the relatively recently introduced dark mode, work

Table of contents

Motivation

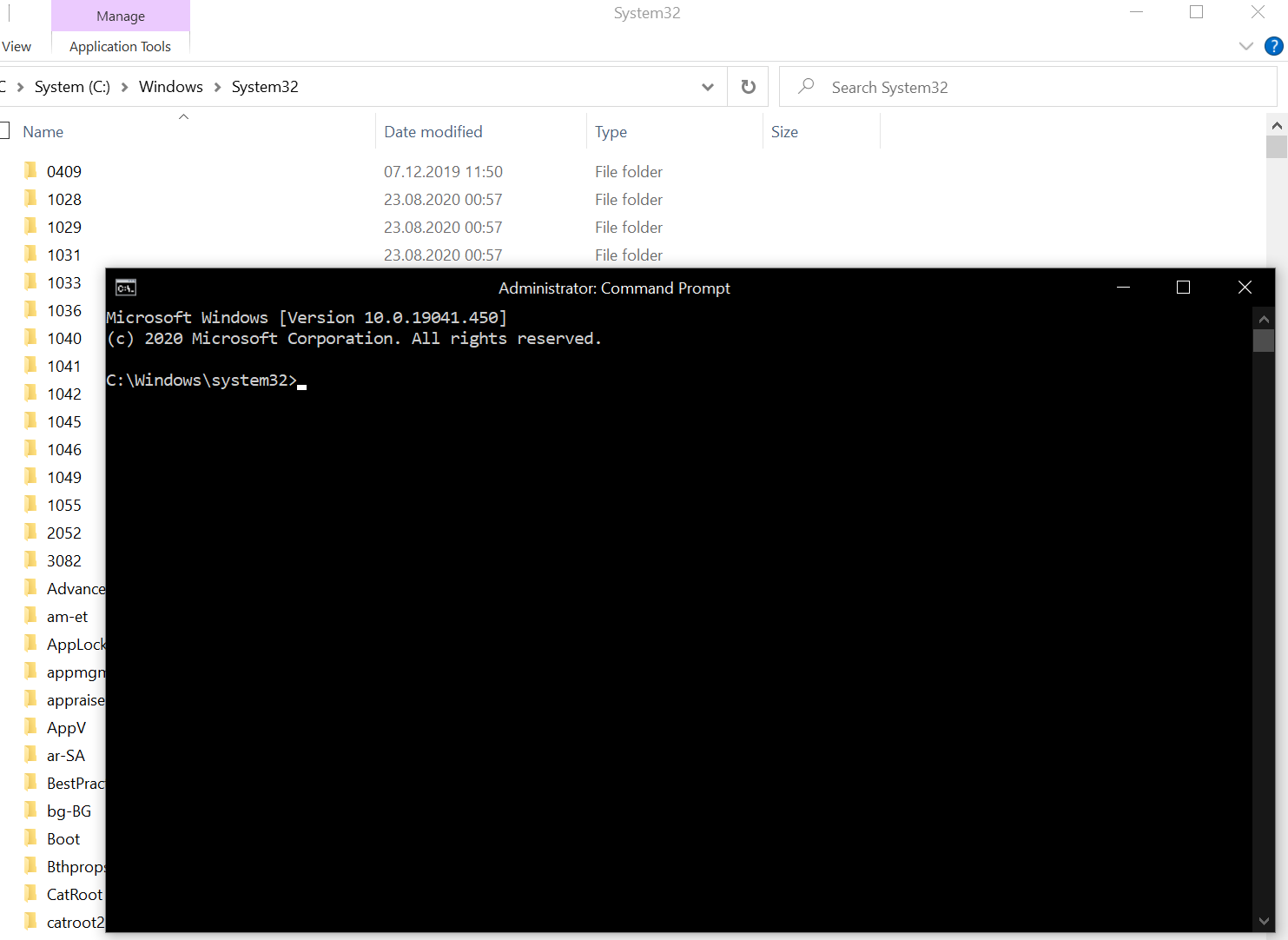

We all know the deed: we have our command windows set to black/dark color, yet when you open them in Windows 10, you’re greeted by this abomination:

White title bar and light scroll bars when all the window is black is horrible. Note that this happens only if you use the light theme for applications in Windows 10. If you switch to dark, then all command windows get a nice black title bar, and a dark gray scroll bar. You could enable the dark theme in Settings, but that’s system-wide, meaning that it affects all apps. For me, I don’t like it for all apps, it just seems it would be perfect for the command window. So, how to do it?

Analysis

Static analysis

Preamble: Set title bar color

Firstly, I don’t know of any setting in the terminal, or within Registry, that allows you to do this only for this window. Secondly, I have recently learned that an application can request its title bar to be drawn with the dark theme on Windows 10, so it seems that an app can request and gets the dark color palette without it being applied system wide. How do you do it? A user on StackOverflow mentioned some undocumented behavour with DwmSetWindowAttribute: use dwAttribute 20 (0x14) in Windows 10 2004, or 19 (0x13) in versions prior, and a pvAttribute of type BOOL set to TRUE. This will have DWM draw the title bar black, so using the dark color scheme:

BOOL value = TRUE;

DwmSetWindowAttribute(

hWnd,

20,

&value,

sizeof(BOOL)

);

Okay, so let’s look on some assembly. But what’s the process responsible? Well, in Windows, conhost hosts all the consoles (think cmd, PowerShell, wsl etc) and draws their windows. For static analysis, I recommend Ghidra.

Introduction

Ghidra, which touts itself as more than a disassambler, as its authors, the National Security Agency, mention on its web site it being a a software reverse engineering (SRE) framework is an excellent tool; it is free to use and released under Apache License 2.0. In my opinion, it is an excellent tool for the price (free), and a great contribution to this scene. IDA Pro is another great alternative, but just consider its price before deciding which one to use. I’ll help you a bit: $1879 for IDA Pro, plus $2629 for the amd64 decompiler we need for this, so we are talking about $4508 excluding taxes.

Symbols

I opened conhost.exe in Ghidra. Before analyzing, make sure to download the symbol file (File - Download PDB File… - have it use the symbol name specified in the file, and use the URL provided in the file - these are questions that Ghidra will ask). Symbol files contain adnotations to particular “objects of interest” in an executable. Without them, functions get generic names, corresponding to the addresses they references, and so on. It is not impossible to statically analyze executables without symbols, in fact most of the times, you won’t have symbols available, but when you do, they can help a fair bit. For all system files, Microsoft provides symbol files. From the point of view of doing static analysis, symbols are the next best thing to have to headers files that you have, for example, with Linux. While header files are actual source of the program, symbols just annotate specific stuff on the final binary (or assembly).

Initial analysis

Next, go to Analysis - Auto Analyze, leave default options checked, and click Ok.

Now, go to Search - Program Text. Search for “dark”, in program database, search type functions. Search all. One entry returns (TrySetDarkMode). Double click on it. Now, if you look at the right, Ghidra is nice enough to show you some pseudocode of the assembly, which is pretty useful for understanding the flow of the program. It is not perfect, but it is pretty useful. First off, let’s note down that this function takes 2 parameters and returns some number.

Next, there are 3 function calls that have a weird name (ImgDelayDescr_IAT@1400ca5f8, … etc), but if you click on it, the relevant location in the assembly will be shown, and the function is revealed as undefined_imp_load_SetWindowTheme…. So, we are talking about SetWindowTheme. The second one is a call to the same SetWindowTheme. This function applies a particularvisual style to the application. If you look, there is an if (local_res8[0] == 0): one branch (for when local_res[8] is 0) calls SetWindowTheme(param_2, L"", NULL), while the other calls SetWindowTheme(param_2, L"DarkMode_Explorer", NULL). So, the way it looks to me, after checking that variable (local_res8[0]), if it is set to 1, it loads a DarkMode_Explorer visual style, which I found out from another Stack Overflow thread is actually the dark visual style built-in desktop applications start to support (for example, Explorer uses this as well when the theme is set to dark). Immediatly after the if block, the code calls DwmSetWindowAttribute(param_2, 20, &local_res8, sizeof(local_res8[0])). So, a dwAttribute of 20, and a pvAttribute of 1 or 0, setting the dark or the light title bar, respectively. The next if block is there if this call fails, and is there to call DwmSetWindowAttribute with dwAttribute 19, as it was in prior Windows 10 versions. Also, by doing this analysis, we can note that param_2 is probably of type HWND.

ShouldAppsUseDarkMode

Alright, it all makes sense. So, the logical step now is to find where that local_res8[0] variable is set. Scrolling to the top of the pseudocode, we see the variable is set to 1 initially, so if we jumped straight to the code blocks mentioned above, we’d get the dark theme actually. There’s not much between that and the top of the code, so let’s try to understand this as well. There’s a check whether the value in the first parameter of TrySetDarkMode is 0. The else branch is more interesting: if *param_1 points to some (apparently) valid module (say, a DLL loaded in memory), it gets the address of ordinal 132 (0x84) in that module (using GetProcAddress), and calls the function at that address with no parameters, storing the result in cVar1 (which is of type char, so one byte, like BYTE, or BOOL). So, something like this:

BYTE (*function)();

function = (BYTE(*)())(GetProcAddress(param_1, 0x84));

BYTE cVar1 = function();

Okay, now we are also able to reconstruct the signature of TrySetDarkMode: LONG TrySetDarkMode(HMODULE *param_1, HWND param_2);. Do note that param_1 is a pointer to an HMODULE. A quick pattern for identifying dereferencing pointers and then calling a function with the data we got as a paramater are instructions like move rcx, [rcx].

Next, what could function be? That same Stack Overflow thread points to some project that figured out some of the unnamed exports from uxtheme. According to that, at ordinal 132 (0x84) is exported a function called ShouldAppsUseDarkMode which takes no parameters, and returns a bool. This probably is a function that tells apps whether the system is using dark mode or not. Okay, so the pseudocode above stands like this:

BYTE (*ShouldAppsUseDarkMode)();

ShouldAppsUseDarkMode = (BYTE(*)())(GetProcAddress(hModule, MAKEINTRESOURCEA(0x84)));

BYTE cVar1 = ShouldAppsUseDarkMode();

_IsHighContrast

But am I certain we are actually talking about param_1 having the address of uxtheme? Well, not 100%, but logically, the next if statement makes it looks so. It checks whether cVar1 is 0, or whether the *_IsHighContrast function return true, and sets local_res8[0] to 0. So that’s what triggers the use of the light theme. We know cVar1 is set by that supposed call to ShouldAppsUseDarkMode, so let’s look into _IsHighContrast, if the name is not obvious enough. Double click its name in pseudocode, it jumps to some code that calls the SystemParametersInfo function, basically querying whether the system is using a high contrast theme or not.

The pseudocode is a bit inexact here, because it does not know about the HIGHCONTRAST structure the call to the function will fill, if supplied with the SPI_GETHIGHCONTRAST parameter (0x42), as is the case. If you look on the disassembly, you see it allocates a HIGHCONTRAST structure on the stack. The local_18, local_14, and local_c “variables” are members of the structure. A better looking pseudocode would be:

HIGHCONTRAST stHC;

stHC.cbSize = sizeof(HIGHCONTRAST); // local_18 = 0x10;

stHC.dwFlags = 0; // local_14 = 0;

stHC.lpszDefaultScheme = 0; // local_c = 0;

BOOL uVar1 = SystemParametersInfo(SPI_GETHIGHCONTRAST, sizeof(HIGHCONTRAST), &stHC, 0); // uVar1 = (*(code *)__imp_SystemParametersInfoW)(0x42,0x10,&local_18,0);

BOOL bVar2 = 0;

if (uVar1)

{

bVar2 = stHC.dwFlags & HCF_HIGHCONTRASTON // bVar2 = (byte)local_14 & 1; - this will be 1 if high contrast is set, as HCF_HIGHCONTRASTON indicates

}

return bVar2;

Conclusion

Fine, so if _IsHighContrast tells the system uses a high contrast theme, or ShouldAppsUseDarkMode tells that apps shouldn’t use dark mode, we set cVar1 to 0, which futher down will make the program use the light mode. But recall, we are not certain we are actually calling ShouldAppsUseDarkMode. How can we be 100% certain? Well, we have 2 options:

- Continue our static analysis. In Ghidra, we can right click the name of a symbol, go to References, and choose Find References to. We could identify the places that explicitly call TrySetDarkMode, and look whether something like

GetModuleHandle(L"uxtheme.dll")is called there. But sometimes, and even in this case, this becomes tedious if the thing we are looking for does not come up immediately. We have to look though tons of assembly, and the pseudocode is not always very good. Fortunately, there is another strategy. - Attempt to dynamically analyze the code. Debug the process and break when TrySetDarkMode is called, and inspect the value *param_1 and determine if it is pointing to uxtheme.dll. This works best when the debugged function is not called from a lot of places. As you will see bellow, this is advantageous in this situation, so we will go this route.

Dynamic analysis

Preparation

In our case, right click on TrySetDarkMode name in Ghidra, go to References, click Find References to. By applying the same procedure, we can determine this approximate call tree:

TrySetDarkMode

- MakeWindow

- CreateInstance

- InitWindowsSubsystem

- ConsoleInputThreadProcWin32

- InitWindowsSubsystem

- CreateInstance

- ConsoleWindowProc

- ?s_ConsoleWindowProc

As you can see, there are not a lot of places where the function is called from. What you have to note though, is that this are all explicit calls. If some variable holds a pointer to TrySetDarkMode at runtime and calls it, we obviously cannot determine that using Ghidra statically beforehand using the procedure above. In fact, you see how I stopped at ConsoleInputThreadProcWin32, and ConsoleWindowProc, that’s because Ghidra did not find any further references to that. It means that it is not called explicitly from code, but by storing a pointer to those functions in some variable and calling that. When you get to situations like this, where you do not know exactly what calls something, it is useful to think and try to understand the flow of the program. Here is my assumption:

-

ConsoleWindowProc is the window procedure of the main window. It was probably assigned so when registering the window class. Indeed, its sole reference is when the ?s_RegisterWindowClass is called. That in turn is only called by CreateInstance. So the tree converges to the tree of MakeWindow. Lets’ look into that.

-

MakeWindow is called initially, when starting up conhost and a window is created on screen. Maybe a thread is created by WinMain that runs this procedure as a starting point. We get this tree:

?s_ConsoleWindowProc

- CreateThread in Start@ConsoleInputThread

- CreateConsoleInputThread@InteractivityFactory instantiates ConsoleInputThread class

- LoadInteractivityFactory instantiates InteractivityFactory class

- A bunch of Locate… functions

- CreateConsoleInputThread

- ConsoleAllocateConsole

- ConsoleHandleConnectionRequest

- ConsoleIoThread

- ConsoleCreateIoThreadLegacy

- wWinMain

- StartConsoleForCmdLine

- wWinMain

- ConsoleCreateIoThreadLegacy

- ConsoleIoThread

- ConsoleHandleConnectionRequest

- ConsoleAllocateConsole

- LoadInteractivityFactory instantiates InteractivityFactory class

- CreateConsoleInputThread@InteractivityFactory instantiates ConsoleInputThread class

All that’s left unexplored are those Locate… functions, yet I do not think it is necessary. I am fairly certain that my assumption is correct.

- CreateThread in Start@ConsoleInputThread

This was all determined by using the Find Reference to function. That alone. So what’s happening after all? Well, I think that TrySetDarkMode is called initially, when creating the window, and whenever a theme change occurs (when that happens, a WM_WININICHANGE message is sent, with lParam set to “ImmersiveColorSet”, according to here). Indeed, if we explore ConsoleWindowProc a bit, we find that at some point, uVar19 is checked against 0x1a, which is the value of WM_WININICHANGE. Further above, uVar19 is puVar14, and puVar14 is param_3, which in a window procedure is wParam, so it all makes sense. When the check succeeds, conhost invokes TrySetDarkMode regardless of the lParam value.

ASLR and PIC

Okay, so back to the original question, how do we identify if we are calling ShouldAppsUseDarkMode using dynamic analysis? Well, we could use a debugger. Break before calling GetProcAddress and note down the address. Then, inject a DLL in the address space of the process and check the address we get for GetModuleHandle(L"uxtheme"). If the two addresses match, we are talking about param_1 being the address of uxtheme. But, wait, is injecting into the actual address space of the program really necessary? Well, as far as I understand it:

-

libraries have a preferred base address - that’s an address that they recommend the loader to load them at; the loader is free to respect this, or just load at a different address (for example, it may be that the requested address is already occupied by something else), fixing the containing addresses in the process

-

one use case where the system may not load the library at its preferred base address is when a nowadays common security feature called ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) is active (it is on by default since Windows Vista); ASLR randomizes the addresses of different sections of code throughout an executable, including the base address (and subsequently, rest of the section addresses) of a loaded library

-

system libraries on Windows are not compiled as aware of what is known as position independent code (PIC/PIE), which means that code sections cannot be relocated freely; so, the loader can relocate the base address, compute the rest of the addresses that may change because of this, but cannot shuffle program sections around

-

okay, why is this important? Well, randomizing where the loader loads libraries every time a library has to be loaded means applications cannot share loaded DLLs; sharing a single memory copy of a loaded DLL between multiple applications has a tremendous speed and size benefit for applications, as that makes loading way faster, not mention eating way less memory, than copying the same information each and every time to different parts of the memory, and loading it from (slow) disk storage each and every time

-

so, to retain the speed benefit and do not impact memory too much, the loader could, say, load the library randomly for the first 3 applications using it, and then, for the fourth one, map library sections to already loaded sections from the address spaces of the 3 previous applications, randomly. An example could be:

Let’s say DLL 1 has a preferred base address of 0x100. That means section A is expected at 0x100, section B at 0x110, and section C at 0x120 (for the sake of simplification, a 0x10 difference between sections). If the loader were to randomize the base address, each section would get a different address, but at the same distance from the base address, for example, if it relocates the DLL when loaded in Application 1 at 0x10, A would map to 0x10, B to 0x20, and C to 0x30. The same for the rest, 2 and 3. Now, the problem with 4 is that if the loader randomizes its loading by mapping sections to different addresses from the previous 3 sets, it could break the relative difference between sections (see how B-A is -0x40 on Application 4). That wouldn’t be a problem if the code was position independent, but as I said, system libraries on Windows are not PIC (yet). So we cannot apply this strategy for them.

- so, what’s there to do? Loading randomly each time would still hurt performance too much. Well, the way ASLR on Windows works nowadays is that the first time, it randomizes the load of a certain (non-PIC aware) library. Subsequent loads will use the same addresses as the first one, sharing the in memory library with the first application. That memory location exhibits a copy-on-write behavior. That means that for reading, all applications read from the same memory location, but as soon as one of the applications rewrites the executable sections of the said library (by hooking a function using a trampoline, for example), Windows will copy the modified library somewhere else and use that for that specific application, leaving the original untouched for the rest - that’s why one application cannot hook a library system wide. This all happens transparently to running applications. When all applications that use a certain library exit, the library is discarded from system memory. Windows is now able to re-randomize the address for an eventual future load of it. It’s been observed that on Windows 10, the system, weirdly, waits a bit more before re-randomizing an unmapped library, as specified here.

- certain system libraries will pretty much be there for the lifetime of the session; for example, every application that does some sort of system call directly or indirectly will load ntdll.dll. There’s always going to be at least a running application using that at any given time. This logic works out for most system libraries. So, what the above behavior generates is that system libraries load at randomized addresses, but that address is the same between processes.

- for our case, uxtheme.dll is loaded by most apps, as most apps use visual styles. Also, as long as there is an application that has loaded it, if we start another one that loads it, the address of uxtheme.dll will be the same between the two (asterisk, unless some other condition required the loader to relocate it for one of the two applications).

- tl;dr libraries are loaded randomly, but at the same random (that should be bolded, because some folks think that ALSR is the universal anti exploit fix).

Strategies

So, for confirming that we are indeed in ShouldAppsUseDarkMode from uxtheme.dll, we can develop a few strategies:

- Knowing that base addresses for common libraries most likely don’t change between application runs, inject the process (using the classic CreateRemoteThread technique), and note down the address reported by

GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"uxtheme"), MAKEINTRESOURCEA(0x84)). Next, rerun the process under the debugger and compare the previous address with what the debugger reports. If you want to learn about injecting other processes, check out my other applications where I exploit this a lot, for example WinCenterTitle, WinOverview2, Trivial Network Load Balancer (here I hook remote processes manually, without the help of any library, using a static analysis procedure similar to what has been described above). - Taking into account more from the above, just run the process once under the debugger, and start our own process that calls

LoadLibrary(L"uxtheme"); GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"uxtheme"), MAKEINTRESOURCEA(0x84)). Again, compare the address from the debugged console to what we get in our process. - Run the process once in the debugger, and from our own app, use EnumProcessModules to enumerate the modules loaded by conhost. The function returns a list of HMODULES, so a list of addresses (in the address space of the remote process). Now having the address of uxtheme.dll, break calling the supposed function from uxtheme.dll in TrySetDarkMode. Then, step into. If we go to an address after the address we got for uxtheme.dll, we are almost sure we are in uxtheme.dll. We have to check we are before the address or after the address of any other module.

- Techniques above have their uses depending on the situation. It is useful to know all of that in order to understand how things really work under the hood, and how we can link together knowledge we have to do interesting things. All the talk above is not strictly necessary to answer the strict question of where does the code jump on that call. To answer that without bothering about anything else, just debug conhost, break before the call, step into. Since we are in a debugger, it knows what modules are loaded where. Consult that and we are done.

Debugging

A shortcoming of Ghidra when compared to IDA Pro is that it does not come with a debugger. Or that it does not integrate with one as seamlessly as IDA Pro. But we can forgive them for the money we paid. Instead, a free debugger we can use is Microsoft’s, which is available in Visual Studio if you install the C/C++ desktop development workload.

Okay, so let’s attach Microsoft’s debugger to conhost. For this, create a folder, place a copy of conhost.exe in it, and a copy of the symbol files downloaded with Ghidra for conhost.exe previously (conhost.pdb). Now, open Visual Studio, continue without code, File, Open, Project/Solution and choose conhost.exe in the browse window. Now, click Debug, Step Into. The debugger will launch the process and break on its first instruction (in wWinMain). Now, click “view disassembly”. Let’s set a breakpoint when we enter TrySetDarkMode function. There are 3 ways to go there:

- In the Address field, type

Microsoft::Console::Interactivity::Win32::WindowTheme::TrySetDarkMode(you can make out this pattern from the function name shown in Ghidra. - Another trick is to take the last bytes of the address shown in Ghidra and substitute them in the address shown in Visual Studio. For example, TrySetDarkMode appears for me, in Ghidra, at 0x140017978. Now, in Visual Studio (so, on the live process), TrySetDarkMode is at 0x7FF7B5BC7978. In both, 7978 is the same. So, the process would be, take 0x140017978, remove the first part, end with 0x7978. Take any address from Visual Studio where you may have landed, like 0x7FF7B5BCBEC0, take out 0xBEC0, and add that 0x7978, and you get to 0x7FF7B5BC7978. Why does this work? Remember, ALSR (or sometimes some other event) randomizes the base address, but the order of sections is the same for non-PIC aware executables, so on a live process, the base address might differ, but if we adjust our static executable to that dynamic new base address, by adding the corresponding offsets we end in the same place. This is the process in 3 done manually.

- If you are not lazy like I am initially, step 2 is an actual feature of any tool like Ghidra - it is called image rebasing. In Ghidra, you can rebase an image by going to Window - Memory Map. Click the house icon, and type the base address you get from Visual Studio: Debug - Windows - Modules. Look for the conhost.exe module in there, and write down the start address. For me, it was 0x7FF7B5BB0000. Type that as ‘home’ in Ghidra. Now, research for ‘dark’ and go back to TrySetDarkMode. The addresses of the live debugged process, and those shown in Ghidra now correspond.

In Visual Studio, set a breakpoint at the first address of TrySetDarkMode (the instruction there is mov qword ptr [rsp+10h],rbx). Now, click F5 to continue the process. It will break there. Recall that TrySetDarkMode has its first parameter set to an HMODULE, supposedly the address of uxtheme.dll. Is that so? According to the x64 calling convention, the first parameter of a function is stored in rcx. To see the values in the registers, go to Debug - Windows - Registers.

What we have now in rcx does not look like the address of uxtheme.dll. True, but remember (from what Ghidra taught us) that the first parameter is a pointer to some address, not the actual address. If we look on the disassembly, we see 4 instructions further down, the value at the address in rcx is moved to rcx (mov rcx, [rcx], a common pattern for this type of stuff). Press F11 4 times to get there. Inspect the value in rcx. When I did this, I got 00007FFB39CC0000. Now, click on Debug - Windows - Modules, and look for uxtheme.dll there. Identify the starting address in the Address column. The two numbers match, so my assumption was correct, the first parameter is the address of uxtheme.dll. If we want, we could step over (F10) a bit more until the procedure we got using GetProcAddress is called, and then step into (F11). We get into LdrpDispatchUserCallTarget Step thought that with F11 until we make a jump. Then, Visual Studio wants us to load the source code for “shell\themes\uxtheme\immersivecolor.cpp”, which is clearly from uxtheme. We do not have that (what a surprise), so we refuse the request. So, we are back on disassembly. What’s the address of the instruction? For me, it is 00007FFB39CCA950, which falls within the range of uxtheme.dll that is reported to be 00007FFB39CC0000-00007FFB39D5F000 in the Modules tab. So yeah, I am pretty sure my assumption was correct.

That was the case of calling TrySetDarkMode when creating the window. Now, press F5 to continue debugging and then change apps to dark mode from Settings - Personalization - Colors and notice how the breakpoint is hit again. This is the case when TrySetDarkMode is called from the window procedure of the window, after being notified about the theme change by the system.

It feels good to be right. But actually, what’s that LdrpDispatchUserCallTarget? I said I was calling ShouldAppsUseDarkMode, what’s up with that? Good question, I was a bit puzzled at first. Well, something injected our process and set some kind of trampoline compared to what we have in the static binary. Woah, so is the computer infected with some kind of a virus? Well, not really, that ‘something’ is the operating system. What we see here is a pretty useful memory check and sanitization mechanism that’s called Control Flow Guard in Windows 10. This is a feature of the kernel that works in tandem with an executable image that is prepared for supporting this (use “/guard:cf” when compiling with Microsoft). The runtime component maintained by the kernel determines valid indirect call targets and checks whether an indirect call is valid. That’s exactly what happened in our call, as conhost calls an address obtained dynamically using GetProcAddress, not some explicit function (like printf etc). The purpose of CGF is to prevent attacks from messing with the address intended to be called, as conhost wants to call ShouldAppsUseDarkMode, not some other thing. So, at load time, the loader, with support from the kernel, patches a CGF aware executable to support its functions, in addition to the other common tasks it performs.

Conclusion

Okay, so, with all this information acquired, what’s the conclusion? Well, what I did was to neuter the call to ShouldAppsUseDarkMode. As I am not using a high contrast theme, the if statement will never be true, and the local_res8[0] flag will remain set to 1, which will make conhost use dark mode. You could of course patch out the call to _IsHighContrast as well, also the call to GetProcAddress etc. That’s up to you. Personally, I prefer to patch as few as necessary for what I am trying to achieve to work, so that I could reapply it quickly in case of an update to the executable.

Binary patching

So, let’s patch out the call to ShouldAppsUseDarkMode. In Ghidra, go to that line. The bytes are: ff 15 b3 2e 08 00. These have to be replaced by a nop (0x90). Copy a few more surrounding bytes so that we get less matches when looking though the file. I copied this string: 881d9e530a004885c07477ff15b32e08009084c0. So, open the executable using a hex editor (I use HxD). Go to Search - Find - Hex values. Paste the string from before. Click Search all. If only one match is returned, it is fine, if not, include more bytes from the listing in Ghidra. Identify ff15b32e0800 and replace it with 909090909090. Save and you’re done, execute conhost.exe directly to confirm. To apply this system wide, copy this file to C:\Windows\System32. To be able to actually replace the file, take ownership of the original conhost.exe. That’s it.

The result:

In the future, I’d like to add here about how to develop a good strategy around binary patching. Answering the questions: how do we form the search pattern so that it is most unlikely to change in future versions of the program? But I think that is a topic for another revision of this, so until then, enjoy not being blinded when working with the terminal.